Limits to Growth - 42 years on

In response to a recent observation I encountered, that we talked about all this 40 plus years ago, and it was portrayed as urgent then, I've heard it all before... I'm choosing to focus on the most well known set of predictions from about 42 years ago, made in the book 'Limits to Growth'. For its 40th anniversary, work was done revisiting its predictions, and assessing if its predictions were as wildly inaccurate as they were often portrayed to be. Here's a summary of that work:

Looking Back on the Limits of Growth

Recent research supports the conclusions of a controversial environmental study released 40 years ago: The world is on track for disaster. So says Australian physicist Graham Turner, who revisited perhaps the most groundbreaking academic work of the 1970s, The Limits to Growth.

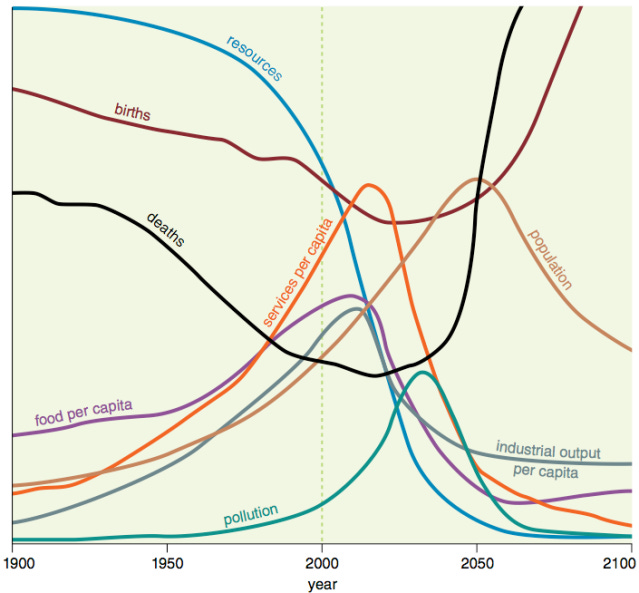

“There is a very clear warning bell being rung here. We are not on a sustainable trajectory.”Written by MIT researchers for an international think tank, the Club of Rome, the study used computers to model several possible future scenarios. The business-as-usual scenario estimated that if human beings continued to consume more than nature was capable of providing, global economic collapse and precipitous population decline could occur by 2030.

However, the study also noted that unlimited economic growth was possible, if governments forged policies and invested in technologies to regulate the expansion of humanity’s ecological footprint. Prominent economists disagreed with the report’s methodology and conclusions. Yale’s Henry Wallich opposed active intervention, declaring that limiting economic growth too soon would be “consigning billions to permanent poverty.”

Turner compared real-world data from 1970 to 2000 with the business-as-usual scenario. He found the predictions nearly matched the facts. “There is a very clear warning bell being rung here,” he says. “We are not on a sustainable trajectory.”

* * *

Source: http://bit.ly/W3ah0L And from the 'Our Finite World' blog, which features regularly in my attempts to summarise what's going on:

It seems to me that we may be reaching “Limits to Growth,” as foretold in the book by the same name in 1972. The book modeled the consequences of a rapidly growing world population and finite resource supplies. A wide range of scenarios was tested, but the result in nearly all scenarios was overshoot and collapse, with the timing of collapse typically being in the 2010 to 2075 time period.

The authors of Limits to Growth did not model the full interactions of the system. One element omitted was how debt would impact the system. Another item omitted was how prices for oil and other resources would affect the system. If a person follows through the expected effects of high oil prices and debt, the financial system would appear to be the most vulnerable part of the system. The financial system would also appear to be what telegraphs problems from one part of the system to another. Unless a solution is found, failure of the financial system could ultimately bring down the whole system. Background Newspapers print endless articles about the need for economic growth, and the need for return to economic growth. But if economic growth really takes resources of some sort–coal, or oil or copper, or fresh water to produce goods and services–it stands to reason that at some point, the resources needed for economic growth will run short. This is especially true for resources that are used up when they are burned, like coal and oil. Besides the issue of inadequate resources, growing pollution can also interfere with economic growth. As the world is filled with more people, and resources become shorter in supply, pollution becomes more of an issue. Logically, at some point we can expect to run into limits that are impossible to get around. One of these limits may be inadequate funds for investment in extraction of resources.

...In my view, what has happened since 2003-2004 is very similar to the effect a person might expect from Liebig’s Law of the Minimum, if oil is a necessary component of the economy, and high oil price signals that too little oil is reaching the system. In agricultural science, Liebig’s Law of the Minimum states that the amount of plant growth is governed not by the total resource available, but by the amount of input of the needed resource in least supply (for example, nitrogen, phosphorous, or potassium). In other words, it isn’t possible to substitute one type of fertilizer for another; similarly, it isn’t possible to substitute one energy product for another in the short term. Instead output contracts, if oil is too high-priced. In a way, this contraction might be seen as a dress rehearsal for the ultimate contraction which Limits to Growth models have suggested will eventually arrive. I am sure that some would say that oil supply would need to actually decline, for there to be a problem. Since the Limits to Growth model does not look at resource prices, it does not consider this detail. It would seem to me that by the time world oil supply actually declines, the world may already be in a major recession, which does not allow prices to rise high enough to keep production up. Connection with Debt What relationship does debt have to the economy? 1. Economic growth enables debt, because in a growing economy, the greater amount of resources available at a later date make it much easier to repay debt with interest. I have shown an illustration of this several times.

The above relationship does not mean that debt would disappear completely in a shrinking economy. There would still be some situations where debt would be used, such as in short term loans to facilitate trade, and in situations where high rates of return can be assured. 2. Additional debt enables GDP to grow more rapidly than it otherwise would, because GDP is a gross measure–a measure of what an economy produces and sells–and having more debt helps in two respects: a. Additional debt helps the company extracting the resource or doing the manufacturing, by giving the company additional funds to work with–to purchase plant and equipment, or to hire consultants. It doesn’t have to wait and only use accumulated profits to fund new ventures. b. Additional debt helps the potential buyer of goods, because the buyer can pay for the new item purchased (automobile, refrigerator, or house, for example) over a period of years while using the new product. But higher oil prices tend to be associated with higher food prices. (See Figure 6, below.) When prices of oil and food rise, consumers (except for those making more money because of higher oil and food prices) tend to cut back on discretionary spending. This cut-back in spending leads to lay-offs and recession in discretionary segments of the economy. Some laid-off workers default on their debts, and businesses scale back their plans for expansion, because of the “bad economy”. As a result, they too need less debt. So debt works well in a growing economy, but once an economy hits high oil prices and recession, debt works much less well. An economy has positive feed back loops from debt in a growing economy, but once oil limits (in terms of high prices) start to hit, feedback loops work in reverse–consumers and producers see less need for debt, and in fact, may default on past loans. Shrinking debt levels make it increasingly difficult for GDP to grow.

The following excerpt has some interesting observations regarding the omission of debt on the model's predictive power:

...Impact of Omission of Debt and Prices in the Limits to Growth Model Figure 1 clearly shows a tendency toward overshoot and collapse, based on the Limits to Growth model as it was originally created. The original model doesn’t consider the impact of debt or of resource prices. The omission of debt means that the model doesn’t consider the possibility of moving from an “increasing debt” situation to a “decreasing debt” situation. If such a change takes place about the time resource limits hit, a person would expect sharper peaks and faster declines to the modeled variables. The omission of resource prices means that the model doesn’t pick up the interconnections between high prices for one resource, and a cut back on demand for other resources. We discovered during the 2008-2009 recession that electricity demand dropped at the same time as oil demand. If financial interconnections cause a shortage of one resource to lead to reduced demand for other resources, this may mean that substitution will not will work as well as some hope. Nothing happens overnight with the world economy, so changes are likely to take place over a period of years, rather than all at once. We can’t know exactly what the future will bring, but the handwriting on the wall is worrisome.

Source: http://bit.ly/ofwl2gupdate I hope I've shown that whilst there are some criticisms of the 'Limits to Growth' narrative, it's basic predictions seem to be holding up, as the relentless maths of growth in a finite system place limits on our future economic expansion at best, and quite possibly lead to sharp declines in economic activity in the not too distant future. More from the 40 year update on the original Limits to Growth here: http://www.clubofrome.org/?p=326 Particularly this introduction to the book 'Limits to Growth Revisited' is a good overview of the history: http://bit.ly/1sTcOFy