The decoupling canard won't die...

aka, 'Green Growth is an oxymoron'! I keep coming across people contending that decoupling will allow continued economic expansion, whilst reducing emissions. I put together this summary of rebuttals:

This is a great starting observation from Tim Morgan at Surplus energy economics:

“At the same time, we should dismiss the idea that we can somehow “decouple” the economy from energy. Fortunately, a quite superb recent report from the European Environmental Bureau (EEB) has debunked the concept of “decoupling” so comprehensively that we can defer detailed consideration to a later discussion.

“Our finding is clear”, the EEB report concludes – “the decoupling literature is a haystack without a needle”.

There – political leaders please note – goes your cherished ambition to deliver “sustainable growth”. ‘Sustainable’ is something to which we can and must aspire. But “growth” is not.”

Here’s the direct link to the EEB’s comprehensive debunking of the decoupling canard, summarised as:

Although decoupling is useful and necessary, and has occurred at certain times and places, ‘green growth’ cannot reduce resource use on anywhere near the scale required to deal with global environmental breakdown and to keep global warming below the target of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, the threshold established as part of the Paris Agreement.

This is the conclusion of ‘Decoupling debunked: Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability’. Published by the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), the report reviews the empirical evidence and theoretical literature to assess the validity of the decoupling hypothesis.

The report, whose lead author is Timothée Parrique of the Centre for Studies and Research in International Development (CERDI), finds that there is no empirical evidence supporting the existence of an absolute, permanent, global, substantial and sufficiently rapid decoupling of economic growth from environmental pressures. Absolute decoupling is also highly unlikely to happen in the future, the report concludes.

‘Decoupling debunked’ highlights the need for the rethinking of green growth policies and the urgent necessity to identify alternative approaches that can safeguard prosperity and wellbeing while protecting the environment.

Then there’s this great line of reasoning, again from Timothée Parrique :

“The validity of the green growth discourse relies on the assumption of an absolute, permanent, global, large and fast enough decoupling of Gross Domestic Product from all critical environmental pressures. Problem is: there is no empirical evidence for such a decoupling having ever happened. This is the case for materials, energy, water, greenhouse gases, land, water pollutants, and biodiversity loss, for which decoupling is either only relative, and/or observed only temporarily, and/or only locally. In most cases, decoupling is relative. When absolute decoupling occurs, it is observed only during rather short periods of time, concerning only certain resources or forms of impacts, for specific locations, and with minuscule rates of mitigation.

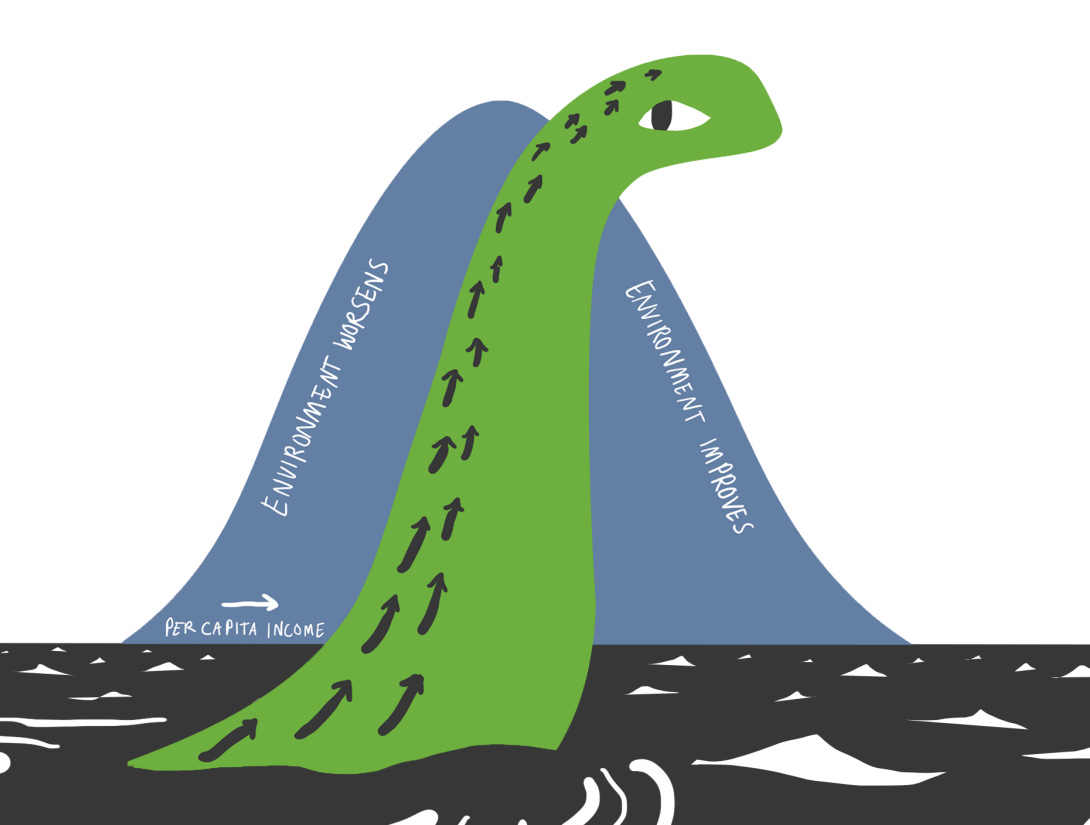

Of course we can bicker about numbers. Perhaps the camera was faulty and the Loch Ness monster is still somewhere to be found. And after all, the lack of empirical support does not suffice to fully dismiss the possibility of decoupling, which some argue could well happen in the future with the right set of policies.

Seven reason why decoupling won’t happen

But that is wishful thinking. In the report, we offer seven reasons to be sceptical about the occurrence of decoupling in the near future:

Rising energy expenditures. When extracting a resource, cheaper options are generally used first, the extraction of remaining stocks then becoming a more resource- and energy-intensive process resulting in a rising total environmental degradation per unit of resource extracted.

Rebound effects. Efficiency improvements are often partly or totally compensated by a reallocation of saved resources and money to either more of the same consumption (e.g. using a fuel-efficient car more often), or other impactful consumptions (e.g. buying plane tickets for remote holidays with the money saved from fuel economies). It can also generate structural changes in the economy that induce higher consumption (e.g. more fuel-efficient cars reinforce a car-based transport system at the expense of greener alternatives, such as public transport and cycling).

Problem shifting. Technological solutions to one environmental problem can create new ones and/or exacerbate others. For example, the production of private electric vehicles puts pressure on lithium, copper, and cobalt resources; the production of biofuel raises concerns about land use; while nuclear power generation produces nuclear risks and logistic concerns regarding nuclear waste disposal.

The underestimated impact of services. The service economy can only exist on top of the material economy, not instead of it. Services have a significant footprint that often adds to, rather than substitute, that of goods.

Limited potential of recycling. Recycling rates are currently low and only slowly increasing, and recycling processes generally still require a significant amount of energy and virgin raw materials. Most importantly, recycling is strictly limited in its ability to provide resources for an expanding material economy.

Insufficient and inappropriate technological change. Technological progress is not targeting the factors of production that matter for ecological sustainability and not leading to the type of innovations that reduce environmental pressures; it is not disruptive enough as it fails to displace other undesirable technologies; and it is not in itself fast enough to enable a sufficient decoupling.

Cost shifting. What has been observed and termed as decoupling in some local cases was generally only apparent decoupling resulting mostly from an externalisation of environmental impact from high-consumption to low-consumption countries enabled by international trade. Accounting on a footprint basis reveals a much less optimistic picture and casts further doubt on the possibility of a consistent decoupling in the future.

Decoupling is a waste of time

As Herman Daly already argued forty years ago, the bet we are facing is similar to Pascal’s Wager. Either we hope that somehow these seven problems will solve themselves, continue growth-as-usual and risk environmental breakdown; or we acknowledge that decoupling is likely to fail with irreversible consequences, follow a precautionary principle approach, and start directly reducing the problematic forms of production and consumption.

Besides, framing these issues as a decoupling challenge is problematic. A weird mix of a Cartesian desire to emancipate humans from nature, coupled with an escape-forward logic. It is not innocent that the term “decoupling” itself comes from the field of electrical engineering. If problems with humans are solved forward with transhumanism, green growth promises a transnatural form of ecological sustainability. Even if it were theoretically possible (which is not), decoupling would still not be a healthy objective.

Instead of a divorce between society and nature, one should rather pursue couple’s therapy to reconcile one with the other, namely figuring out how to ensure the provision of what is required for the “good life” following a principle of prudent stewardship and non-exploitation. The issues we find ourselves in can be solved backward by acting on the elements that created the problem in the first place, namely the choice of countries to pursue economic growth at all social ecological costs.”

And yes, the UK's supposed decoupling had merely shifted the emissions elsewhere :

"The Myth of ‘Decoupling’

To reduce the material footprint of countries, in an effort to prevent crossing the 1.5°C warming limit, governments and financial institutions have looked to the theory of ‘decoupling’. Decoupling is a process that looks to reduce the number of resources being used, whilst maintaining constant gross domestic product (GDP) growth which, within the current form of capitalist governance, is key to sustaining prosperity.

For example, due to “economic structural change, technological advancement and enforcement of environmental regulations” – such as the Climate Change Act of 2008 – the U.K. claims that it has shown evidence of decoupling between 1985 and 2016, as the “GDP per head grew by 70.7%, whilst CO2 emissions fell by 34.2%” (ONS, 2019). Governments point to this evidence to support the maintenance of the free-market consumerist economy, as it seemingly provides evidence that GDP can continue to grow whilst the carbon footprint of the nation is reduced.

However, a recent paper published by the BIOS Research Institute in Finland – a team which has previously advised the UN on emerging biophysical limits to endless economic growth – has reviewed 179 scientific studies on decoupling between 1990-2019 and found that that there is “no evidence” that meaningful decoupling has ever occurred at either a regional or global level (Váden et al., 2020a).

Despite evidence presented by the U.K. government suggesting that decoupling has occurred over the last 30 years, the report found that the reduction in resource use in the U.K. has resulted in a deepening of resource use elsewhere.

Over the past 50 years, manufacturing output in European countries has generally declined, as most have transitioned to becoming predominantly financial and service-based economies. Subsequently, since the 1970s, the U.K. has gone from 6th in the world in manufacturing output, to reaching a low of 11th in 2013 (West and Lansang, 2018). Conversely, China has gone from 5th in the 1970s, to 1st since 2010, overtaking the United States with the largest manufacturing output in the world.

As a consequence, annual CO2 emissions in countries that seek to meet the demands of the global consumerist market, such as China, have significantly increased. Over a 20-year-period, China’s annual CO2 emissions have increased from 3.41 billion tonnes in 1997, to 9.84 billion tonnes in 2017.

Essentially, the dependency of free-market capitalism on increasing levels of GDP has resulted in the perpetuation of an environmentally toxic system of governance, which places production, consumption and wealth above sustainability and human survival.

Therefore, whilst wealthier and more technologically advanced nations are able to improve efficiencies in resource use within their own country, it doesn’t mean that the material footprint is being reduced globally.

“For absolute resource decoupling to make sense as a global goal, we would need a scenario where, in ca. 30 years, the economy produces 2.6 times more GDP out of every ton of material used, under conditions where material use diminishes ca. 40 percent globally. Currently no trends corresponding to this scenario are observable and, to our knowledge, no current proposals with such a level of decoupling have been presented.” (Váden et al, 2020b)"

Here's the references :

Váden et al. (2020a). “Decoupling for ecological sustainability: A categorisation and review of research literature”. Environmental Science & Policy, Vol. 112, pp.236-244. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901120304342?dgcid=coauthor [Accessed 10th August, 2020].

Váden et al. (2020b). “Raising the bar: on the type, size and timeline of ‘successful’ decoupling.” Environmental Politics. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09644016.2020.1783951 [Accessed 10th August, 2020].

Lastly, there’s a very useful critique of the Australian ‘decoupling strategy’ from 2015, published in 2017:

This paper provides a critical commentary on the high profile Australian National Outlook (ANO) Report, published in late 2015 by Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) (Hatfield-Dodds et al., 2015a). The report’s findings were also published in the prestigious, peer-reviewed journal Nature (Hatfield-Dodds et al., 2015c), suggesting that the conclusions are robust and should be accepted. The report argues that with collective effort and sound policy, Australia can ‘achieve economic growth and improved living standards while also protecting or even improving our natural assets’ (Hatfield-Dodds et al., 2015a: 12). The report therefore aligns closely with a broader range of literature arguing that economic growth, no matter how environmentally damaging it has been historically, can be ‘decoupled’ from environmental impacts by way of technological innovation, resource efficiency improvements, pricing mechanisms, and conservation efforts (see Hatfield-Dodds et al., 2015a: 4; see also UNEP, 2011; Grantham Institute, 2013; Blomqvist et al., 2015). The findings of the report are underpinned by several scientific papers that will also be considered throughout our critique (Schandl et al., 2015; Hatfield-Dodds et al., 2015b; Hatfield-Dodds et al., 2015c; Baynes, 2015).

…Lenzen et al (2016) have shown with respect to the carbon intensity of the Australian economy that both the medium and high ANO abatement scenarios require a ten-fold acceleration in technologically driven emission intensity improvement compared to the trend rate over the last three decades. They point out that ‘there was not a single country that, since 1990, has achieved technology-driven emission reductions anywhere near the level’ required in those scenarios (Lenzen et al, 2016: 797). Malik et al (2016)have shown that globally over the same period increases in both affluence and population outstripped technologically driven carbon efficiency gains, resulting in rising emissions. Contrary to the CSIRO, they conclude that supply-side efficiency gains are unlikely to be sufficient to achieve safe carbon reductions and ‘governments may need to actively intervene in non-sustainable lifestyles to achieve emission reductions’ (Maliket al, 2016, 4722).

The same historically unprecedented gains are required with respect to resource efficiency, with Stretch projecting a 4.5% p.a. improvement for the global economy through to 2050. By comparison, a review of the evidence found that resource efficiency improvement from 1980-2009 averaged 0.9% p.a. (Giljum et al., 2009).7 Furthermore, as that review, as well as a more recent UNEP (2016) report found, this efficiency improvement rate masks a more recent efficiency decline since the turn of the century. That is, today the global economy uses more resources per unit of GDP than in the year2000. This means that, far from decoupling – even in relative terms – over the last decade and a half the global economy has undergone a process of absolute material ‘recoupling’.

If we narrow the focus to decoupling trends in OECD nations, it has often been claimed that substantial relative, if not absolute, decoupling of resource use has been achieved. However, Wiedmann et al (2015) has shown that this is only true when using the ‘domestic material consumption’ (DMC) accounting measure which looks at natural resources consumed directly within a given nation. If instead one uses the material footprint (MF) measure, which factors in all the natural resources embedded within imports and exports, and therefore fully accounts for the impact of globalization, the picture looks very different.8 They found, for example, that across the entire OECD for the period between 1990-2005 ‘no improvements in resource productivity at all are observed when measured as the GDP/MF’ (Wiedmann et al, 2015: 6273).

(18) (PDF) A Critique of the Australian National Outlook Decoupling Strategy: A ‘Limits to Growth’ Perspective. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320311527_A_Critique_of_the_Australian_National_Outlook_Decoupling_Strategy_A_%27Limits_to_Growth%27_Perspective [accessed Nov 10 2022].

Great piece, Nathan.

I'm increasingly coming to the conclusion that all such narratives (those that argue for the continuation of 'growth’) are readily accepted by most since they are part and parcel of our denial/bargaining of the bio- and geo-physical limits of existence on a finite planet.

More 'nefariously' these stories are simply marketing/propaganda by the ruling caste and its sycophants to support their primary motivation: the control/expansion of the wealth-generation/-extraction systems that provide their revenue streams and thus positions of power and prestige. Everything, and I mean everything, is leveraged to meet this overarching goal.

For example, the idea that a massive transition to 'green/clean' energy and related industrial products and processes--that are marketed as 'net zero/carbon-free'--can alter our climate trajectory completely overlooks the significant environmental/ecological damages that such a shift would entail.

That the ruling elite has created an Overton Window such that most people buy into this tale and cannot think outside the box created is not surprising. Carbon is our enemy and can be overcome via ‘carbon-free’ thinking and products; anyone who points out the flaws in this narrative are climate change deniers or shills for the fossil fuel energy.

Nowhere in the discussion is a realisation that the knock-on effects of the significant industrial processes that are involved or necessary to transition away from fossil fuels are problematic--in the extreme. Or, that land system changes created because of our constant expansion are detrimental to our hydrological systems and thus creating the extreme weather events we are experiencing—perhaps even more so than ‘climate change’ .

That land system changes are having a significant impact on our weather patterns cannot be considered at all since the idea that we need to stop altering the landscape of our world runs in a diametrically-opposed way from the expansion and growth of our human experiment. And this, of course, undermines the ruling caste’s power base. Better to leverage crises in a way that allows status quo power/wealth structures to be maintained and/or expanded, just as the idea of decoupling does.

The growth imperative must be maintained at all costs and perhaps as importantly the idea/belief that it can be must be adhered to by the significant majority of the population (or, at least, passively accepted) so that there is little to no rejection and thus counter-narratives to it.

For despite the seeming strength of the concept that infinite growth on a finite planet is entirely possible (because of technology and human ingenuity), if a tipping point of the populace comes to understand that our pursuit of growth is what has destroyed vast portions of our planet and other species leading us deeply into ecological overshoot—and subsequently rejects its pursuit--then the entire foundation of the ruling elite crumbles. And we can’t have that!

Better to double or triple down on the propaganda and censor/ostracise counter-narratives, thus allowing the game to go on just a bit longer…

Indeed, clearly marked degrowth and a significant decline in consumerism is required in order to usher in a circular economy that eschews materialism for the sustainability of current and future generations.